The geographic genetic structure, based on sequence variation of an 810 base pair fragment of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene, is described for populations of five subspecies of the Little Pocket Mouse, Perognathus longimembris, from Southern California. One of these, P. l. pacificus (Pacific Pocket Mouse), is listed as Endangered by the U.S. Federal Government. Sixty-two unique haplotypes were recovered from 99 individuals sampled. Phylogenetic analyses of these variants do not identify regionally reciprocally monophyletic lineages concordant with the current subspecies designations, but most haplotypes group by subspecies in networks generated by either statistical parsimony or molecular variance parsimony.Moreover, a substantial proportion of the total pool of haplotype variation is attributed to these subspecies, or to local populations within geographic segments of each, indicating their relative evolutionary independence. The pooled extant populations of the endangered Pacific Pocket Mouse exhibit the same levels of nucleotide and haplotype diversity as other, presumptively less-impacted populations of adjacent subspecies, although the sample from Dana Point, Orange County, has markedly low haplotype diversity in comparison to all others. These populations also show a genetic signature of population expansion rather than one of decline. Both pieces of evidence are at odds with current empirical population estimates, which reinforces the fact that present-day patterns of genetic diversity are the product of coalescent history and will not necessarily reflect recent anthropogenic, or other, perturbations. Comparison of haplotype variation within and among extant populations of the Pacific Pocket Mouse with those obtained from museum samples collected more than 70 years ago suggests that the pattern of population differentiation and diversity was in place before the post-WorldWar II exponential urbanization of Southern California.

Natural resource managers are often challenged with balancing requirements to maintain wildlife populations and to reduce risks of catastrophic or dangerous wildfires. This challenge is exemplified in the Sierra Nevada of California, where proposals to thin vegetation to reduce wildfire risks have been highly controversial, in part because vegetation treatments could adversely affect an imperiled population of the fisher (Martes pennanti) located in the southern Sierra Nevada. The fisher is an uncommon forest carnivore associated with the types of dense, structurally complex forests often targeted for fuel reduction treatments. Vegetation thinning and removal of deadwood structures would reduce fisher habitat value and remove essential habitat elements used by fishers for resting and denning. However, crown-replacing wildfires also threaten the population’s habitat, potentially over much broader areas than the treatments intended to reduce wildfire risks. To investigate the potential relative risks of wildfires and fuels treatments on this isolated fisher population, we coupled three spatial models to simulate the stochastic and interacting effects of wildfires and fuels management on fisher habitat and population size: a spatially dynamic forest succession and disturbance model, a fisher habitat model, and a fisher metapopulation model, which assumed that fisher fecundity and survivorship correlate with habitat quality. We systematically varied fuel treatment rate, treatment intensity, and fire regime, and assessed their relative effects on the modeled fisher population over 60 years. After estimating the number of adult female fishers remaining at the end of each simulation scenario, we compared the immediate negative effects of fuel treatments to the longer-term positive effect of fuel treatment (via reduction of fire hazard) using structural equation modeling. Our simulations suggest that the direct, negative effects of fuel treatments on fisher population size are generally smaller than the indirect, positive effects of fuel treatments, because fuels treatments reduced the probability of large wildfires that can damage and fragment habitat over larger areas. The benefits of fuel treatments varied by elevation and treatment location with the highest net benefits to fisher found at higher elevations and within higher quality fisher habitat. Simulated fire regime also had a large effect with the largest net benefit of fuel treatments occurring when a more severe fire regime was simulated. However, there was large uncertainty in our projections due to stochastic spatial and temporal wildfires dynamic and fisher population dynamics. Our results demonstrate the difficulty of projecting future populations in systems characterized by large, infrequent, stochastic disturbances. Nevertheless, these coupled models offer a useful decision-support system for evaluating the relative effects of alternative management scenarios; and uncertainties can be reduced as additional data accumulate to refine and validate the models.

The conversion of natural habitat to urban settlements is a primary driver of biodiversity loss, and species’ persistence is threatened by the extent, location, and spatial pattern of development. Urban growth models are widely used to anticipate future development and to inform conservation management, but the source of spatial input to these models may contribute to uncertainty in their predictions. We compared two sources of historic urban maps, used as input for model calibration, to determine how differences in definition and scale of urban extent affect the resulting spatial predictions from a widely used urban growth model for San Diego County, CA under three conservation scenarios. The results showed that rate, extent, and spatial pattern of predicted urban development, and associated habitat loss, may vary substantially depending on the source of input data, regardless of how much land is excluded from development. Although the datasets we compared both represented urban land, different types of land use/land cover included in the definition of urban land and different minimum mapping units contributed to the discrepancies. Varying temporal resolution of the input datasets also contributed to differences in projected rates of development. Differential predicted impacts to vegetation types illustrate how the choice of spatial input data may lead to different conclusions relative to conservation. Although the study cannot reveal whether one dataset is better than another, modelers should carefully consider that geographical reality can be represented differently, and should carefully choose the definition and scale of their data to fit their research objectives.

This paper represents a collaboration by conservation practitioners, ecologists, and climate change scientists to provide specific guidance on local and regional adaptation strategies to climate change for conservation planning and restoration activities. Our geographic focus is the Willamette Valley-Puget Trough-Georgia Basin (WPG) ecoregion, comprised of valley lowlands formerly dominated by now-threatened prairies and oak savannas. We review climate model strengths and limitations, and summarize climate change projections and potential impacts on WPG prairies and oak savannas. We identify a set of six climate-smart strategies that do not require abandoning past management approaches but rather reorienting them towards a dynamic and uncertain future. These strategies focus on linking local and regional landscape characteristics to the emerging needs of species, including potentially novel species assemblages, so that prairies and savannas are maintained in locations and conditions that remain well-suited to their persistence. At the regional scale, planning should use the full range of biological and environmental variability. At the local scale, habitat heterogeneity can be used to support species persistence by identifying key refugia. Climate change may marginalize sites currently used for agriculture and forestry, which may become good candidates for restoration. Native grasslands may increasingly provide ecosystem services that may support broader societal needs exacerbated by climate change. Judicious monitoring can help identify biological thresholds and restoration opportunities. To prepare for both future challenges and opportunities brought about by climate change, land managers must incorporate climate change projections and uncertainties into their long-term planning.

One of the biggest threats to the survival of many plant and animal species is the destruction or fragmentation of their natural habitats. The conservation of landscape connections, where animals, plants, and ecological processes can move freely from one habitat to another, is therefore an essential part of any new conservation or environmental protection plan. In practice, however, maintaining, creating, and protecting connectivity in our increasingly dissected world is a daunting challenge. This fascinating volume provides a synthesis on the current status and literature of connectivity conservation research and implementation. It shows the challenges involved in applying existing knowledge to real-world examples and highlights areas in need of further study. Containing contributions from leading scientists and practitioners, this topical and thought-provoking volume will be essential reading for graduate students, researchers, and practitioners working in conservation biology and natural resource management.

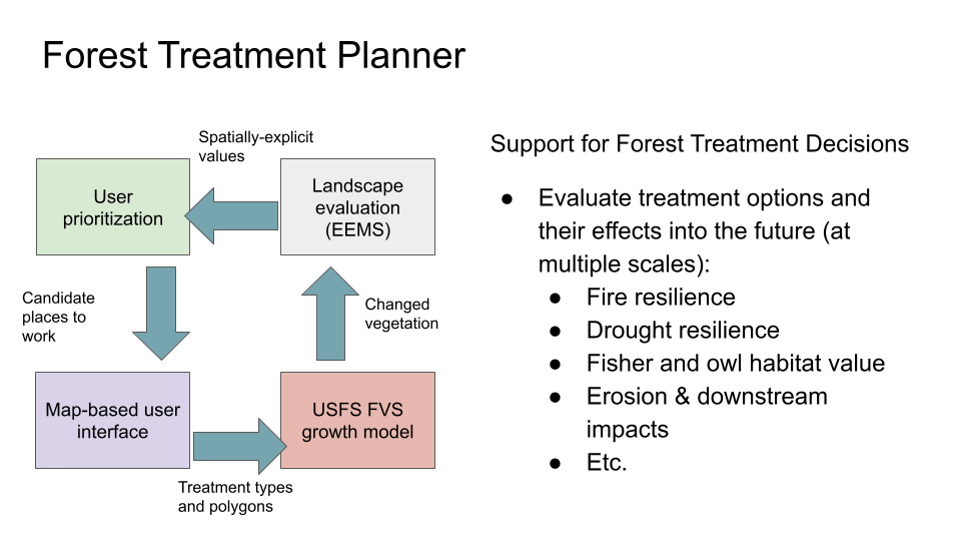

The Forest Treatment Planner was developed to provide forest managers a platform for exploring the potential consequences of different forest management alternatives in both the short and long-term, examine the resource-based trade-offs inherent in any proposed vegetation management action, and clearly substantiate the rationale behind management planning. Originally envisioned as a means to help balance fisher habitat conservation with fuel reduction efforts, the Treatment Planner provides a dynamic link between GIS, the Forest Vegetation Simulator (FVS) modeling software, and any resource model (e.g. habitat, hydrology, fuel, economic) that uses the EEMS (Environmental Evaluation Modeling System) modeling environment. As such, the Treatment Planner is not a model per-se, but a system of communication between existing software that, when used together, can facilitate spatially-explicit comparisons and project refinement. By exporting an FVS output directly into the EEMS modeling environment, this framework allows for a transparent evaluation of the impacts to multiple resource values and a straightforward process for communicating these impacts to stakeholders.

The Treatment Planner supports an iterative process of treatment project simulation, adaptive management, and outcomes analysis, the steps in what we refer to as the “4-Box” decision making framework. The 4-Box model is a conceptual representation of a process designed to help predict future landscape conditions based on simulated management actions and change over time (see Figure). In this process, the forest manager first examines the current conditions of the landscape through the lens of a particular question or management objective (e.g., where is there a need for protection or restoration?). They can then explore the predicted effects of various simulated management alternatives (e.g., thin from above, or thin from below), to see how they would affect the stand structure (e.g., stand density, basal area, and average DBH) over time, both immediately and into the future. Finally, the manager can examine how those new conditions would then affect a particular phenomenon of interest such as, severe fire risk, or wildlife habitat suitability. This process is then repeated under a different set of treatment options (scenarios) to inform the development of an effective management strategy.

Figure 1. The 4-Box model represents a process for evaluating future conditions based on simulated treatments and change over time.

You can check out the detailed steps to use the treatment planner using the document on the file tab. The relevant code for the treatment planner is available at github, click here to download.

CBI worked closely with the Natural Resource Defense Council (NRDC) to integrate relevant spatial datasets to map areas of high value from the standpoint of carbon storage and sequestration, terrestrial ecological value, and aquatic value in support of several NRDC programs, including their 30X30 campaign to protect 30% of nature in the nation by 2030. Click here to learn more about the 30×30 initiative.

Using CBI’s online modeling software called Environmental Evaluation Modeling System (or EEMS), team members were able to construct, review, and modify the models in a rigorous and highly transparent fashion from their individual remote locations. The resulting “living” models can then be used alone or together and in combination with other spatial data (e.g., existing protected areas) to add further context and insight using Data Basin. Data Basin and EEMS were effectively used to help guide NRDC’s important conservation mission.

Landscape connectivity is critical for species dispersal and population resilience. This project is part of the collaborative Landscape Conservation Design (LCD) for the Pacific Northwest coastal ecoregion and conducted in partnership with the North Pacific Landscape Conservation Cooperative. The goal is to identify connectivity pathways and prioritize corridors for 2-4 focal species West of the Cascades in Oregon and Washington. In Oregon, we will work closely with the members of the Oregon Habitat Connectivity Consortium (OHCC) for both the coastal and Willamette valley ecoregions of the state. The methods tested and refined in this project will feed into future Oregon-wide connectivity mapping.

To learn more and explore related maps and datasets, please visit the Data Basin gallery, “Connectivity of Naturalness in Western Washington“. The gallery includes outputs showing the structural connectivity (i.e. naturalness connectivity) for Western Washington.

These data can be used to help guide connectivity conservation efforts. They are the results from the pilot project comparing Omniscape (coreless) and Linkage Mapper (core areas) modeling methods. Extra attention was made to the data inputs and the rigor of the analyses so that the results can be applied, in addition to answering the driving research question.

A Regional Conservation Investment Strategy (RCIS) is a voluntary, non-regulatory, and non-binding conservation assessment that includes information and analyses relating to the conservation of focal species, their associated habitats, and the conservation status of the RCIS land base. The RCIS program, which is administered by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, was created by state bill AB 2087. This conservation strategy is intended to guide conservation investments and advance mitigation in RCIS areas. CBI provided scientific and technical support to ICF International, who led the development of a pilot RCIS for the Antelope Valley in LA County. Implementation of this strategy is intended to sustain and enhance focal species and their habitats in the face of climate change and other stressors such as habitat loss and fragmentation.