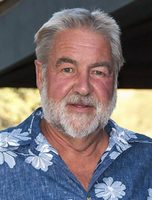

Wildlife conservation lost a leader on August 19, 2022, when Dr. David Graber died suddenly at his home in Three Rivers, California, following a long battle with heart disease. David was a brilliant and dedicated wildlife biologist, innovator, and all-round thought leader at the National Park Service, where he rose to become Chief Scientist for the Western-Pacific Region, before retiring in 2014.

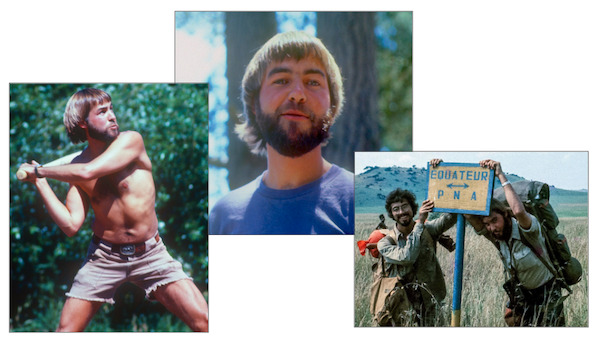

I first met David in the 1970s, when we were graduate students at UC-Berkeley — he working on the bears of Yosemite and me on martens in the Sierra Nevada. I became an immediate fan of David’s freethinking brilliance, amazing vocabulary, excellent writing and speaking skills, and all-round warmth and generosity of spirit. He had an infectious, twinkly smile, a deep laugh, and a sharp and ready wit. In more recent decades, our interactions were mostly at work meetings and conferences, at which I took full advantage whenever possible to be Dave’s dinner partner, so I could hear his ideas and enjoy his witty observations on anything and everything.

Never afraid to pose difficult questions or speak truth to power, David was highly influential in steering the Twentieth Century Park Service toward more effective, science-based management and monitoring practices. Dave was one of the principal advocates and architects of the NPS Inventory and Monitoring Program, and along with Jan van Wagtendonk, he initiated the first systematic Natural Resources Inventory for Sierra Nevada parks. In his position as Chief Scientist, David provided the Park Service with guidance and analysis on a broad range of conservation science and policy issues; he served on endangered species recovery teams for the Channel Island fox, Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep, and northern spotted owl; and to my delight, he represented the Park Service on the Sierra Nevada Fisher Working Group until he retired.

Among his many lifetime achievements, David will always be remembered as the inventor of the bear-proof food storage box, now ubiquitous in campgrounds across the country. His PhD study on Yosemite’s bears changed the thinking about bear management, and consequently how bears and humans interact on federal lands. This substantially reduced incidents of bears ravaging tents and autos, mauling humans, and being shot for it.

But David was more than a conservation scientist. He had an insatiable curiosity and vast knowledge of seemingly everything, from politics and history to literature and the culinary arts. I sometimes sensed that folks were intimidated by David’s scope of knowledge and almost regal bearing when making a point or asking a difficult question. But those of us who knew him well understood that he was just smarter, more knowledgeable, and more passionate about resource conservation than most.

He was also a warm and compassionate friend and family man. I am happy that one of David’s daughters, Sarah Campe with the Sierra Nevada Conservancy, is continuing her father’s pursuit of scientifically sound conservation in the Sierra Nevada, and even happier that CBI gets to work with her on that. Speaking about her father recently, I was deeply honored when Sarah told me that “it tickled him to no end that we worked together.”

Rest in peace, Dave Bear, confident that you made the world better.